The Demise of Ukraine’s “Eurasian Vector” and the Rise of Pro-NATO Sentiment

Before 2014, the majority of Ukrainians did not view the goal of European integration as a “national idea.” Even so, most Ukrainians had positive views about developing relations with and integrating into the EU. And even though former Ukrainian president Viktor Yanukovych refused to accept the idea of joining NATO, he officially maintained EU integration as a priority. In fact, the Yanukovych administration helped finalize and initialed the text of the EU-Ukraine Association Agreement. Yanukovych’s sudden refusal to actually sign it, under Russian pressure, was the spark that set off the mass protests in late 2013 that would become the Euromaidan revolution. The success of the Euromaidan and the ensuing long-awaited signing of the Association Agreement signaled a shift among Ukrainians at both the national and regional level in favor of the EU. In addition, after Russia’s annexation of Crimea, Ukrainians came to favor joining NATO for the first time since independence. Simultaneously, support plummeted for Ukraine’s “Eurasia vector,” i.e., joining Russia-led institutions like the Customs Union/Eurasian Economic Union (EEU).[1]

Ukraine’s Foreign Policy Dualism Has Now Disappeared

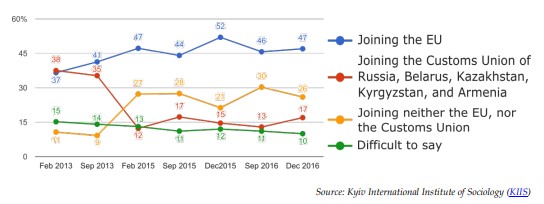

Ukraine’s dilemma, whether to pursue a European or Eurasian vector in its foreign policy, is now off the agenda. The share of EU supporters in Ukraine has increased in recent years, despite some ups and downs (see Figure 1). Support for the Eurasian vector has decreased dramatically in Ukraine, as indicated by the low preference for joining the EEU. The percentage of those in favor of non-alignment has increased, and given Ukraine’s ongoing conflict with Russia, it is unlikely this segment would return to choosing the Eurasian vector. In general, mistrust of Russian geopolitical projects pervades.

Figure 1. What Foreign Policy Path Should Ukraine Choose? (%, Feb. 2013–Dec. 2016)

Source: Kyiv International Institute of Sociology (KIIS)

Before 2014, only among respondents in the 18- to 29-year-old age group was there an absolute majority in favor of joining the EU. By May 2014, according to polls by the Democratic Initiative Foundation (DIF), more than 50 percent of respondents in all age groups were in favor (with the exception of those over 60 years old, where the number of supporters was slightly less).

The Hope for Simultaneously Joining Both Integrationist Projects Is Ruined

Before the end of 2013, geopolitical ambivalence existed among Ukrainians. Part of Ukrainian society did not understand that integration in both directions—with the EU and Customs Union with Russia, Belarus, and Kazakhstan—was not possible. Half of Ukrainians would say “yes” to joining the EU and also “yes” to joining the CU.[2] This situation has completely changed. Already in 2014, polls showed that the idea of membership in the CU/EEU was being strongly rejected. A poll conducted by the Kyiv International Institute of Sociology (KIIS) in December 2016 showed that if there was a referendum on joining the EU, 50 percent would vote in favor and 29 percent would vote against. If there was a referendum on joining the EEU, only 26 percent would be in favor and 59 percent would be against. In practical terms, public support for the multi-vector stance, which was also once popular among Ukrainian officials and politicians, has collapsed.

As a sidenote, Ukrainians are responsive to the European vector when they sense the EU is having a positive impact on sectorial reforms (the EU recently and directly supported reforms in public services, anti-corruption, judiciary, and budget transparency). The recent recognition by the European Commission that Ukraine had fulfilled all of the preconditions for implementing a visa-free regime with the EU opens the way for the introduction in summer 2017 of a “short travel” visa-free regime for Ukrainians going to the EU.

The Most Dramatic Change in Ukraine’s Outlook about the Eurasian Vector Has Been in Eastern and Southern Regions

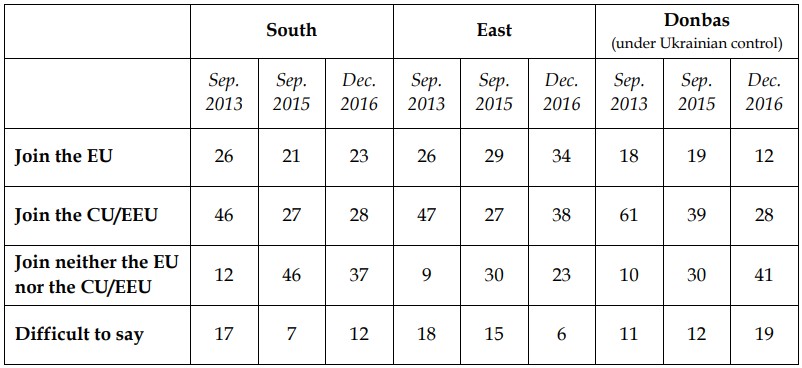

The traditional division of Ukraine into two parts—one strongly in favor of European integration and the other for “Eurasia”—has changed. In the South, East, and Ukraine-controlled Donbas, despite some fluctuations, the populations that supported EEU integration substantially decreased between 2013 and 2016, and those who took a non-allied position toward both unions grew by a factor of three (see Table 2).

Table 1. What Foreign Policy Path Should Ukraine Choose? (Regional Dynamics, 2013-2016)

Source: Kyiv International Institute of Sociology polls (KIIS). Data for Table 2 was recalculated by Tetyana Petrenko and Tetyana Piaskovska from KIIS according to Ukraine’s “macroregions,” which, as defined by DIF, are: Western: Volynska, Zakarpatska, Ivano-Frankivska, Lvivska, Rivnenska, Ternopilska, and Chernivetska; Central: Kyiv city, Kyiv region, Vinnytska, Zhytomyrska, Kirovohradska, Khmelnytska, Poltavska, Sumska, Cherkaska, and Chernihivska; South: Mykolaivska, Odessa, and Khersonska; Eastern: Dnipropetrovska, Zaporizka, and Kharkivska; and Donbas: two-thirds of the Donetsk and Luhansk regions are controlled by Ukraine.

It is apparent that in the South and East, support for the EU and EEU are now close. Even with the difficulties of polling in the war-torn Donbas, the number one choice there is not for the EU or EEU, but for the non-aligned category.

After the Euromaidan’s “Euro-Euphoria,” the Number of EU Supporters in Ukraine Slightly Decreased and Then Stabilized

The primary factors that have most likely contributed to the slight decrease and then stabilization in Ukraine’s public attitudes toward the EU include:

• The Association Agreement may be somewhat connected in public opinion to domestic economic hardships.

• Crises within the EU (Brexit, refugees, etc.).

• Disappointment with the EU on various issues, such as:

- The negative vote in the Netherlands’ consultative referendum on the EU-Ukraine

Association Agreement.

- Delays in introducing an EU visa-free regime for Ukraine.

- Frequent media coverage of the possibility that the EU might reduce or even lift

the economic sectorial sanctions that had been imposed on Russia after its

intervention in Donbas.

The fluctuations in the pro-European integration attitudes should be treated as logical and normal when taking the above factors into consideration as well as Ukraine’s current difficulties with its economy and the war. Even so, a core of supporters for European integration has already formed in the South and East.

As 2017 begins, the general sense is that European integration for Ukrainians is becoming more practical, visible, and directly related to concrete domestic policies and reforms. This follows the Euromaidan, the partial implementation of the Association Agreement, and, perhaps most tangibly, the final stage of the EU-Ukraine visa-free plan.

How Would NATO Fare in a Ukrainian Referendum?

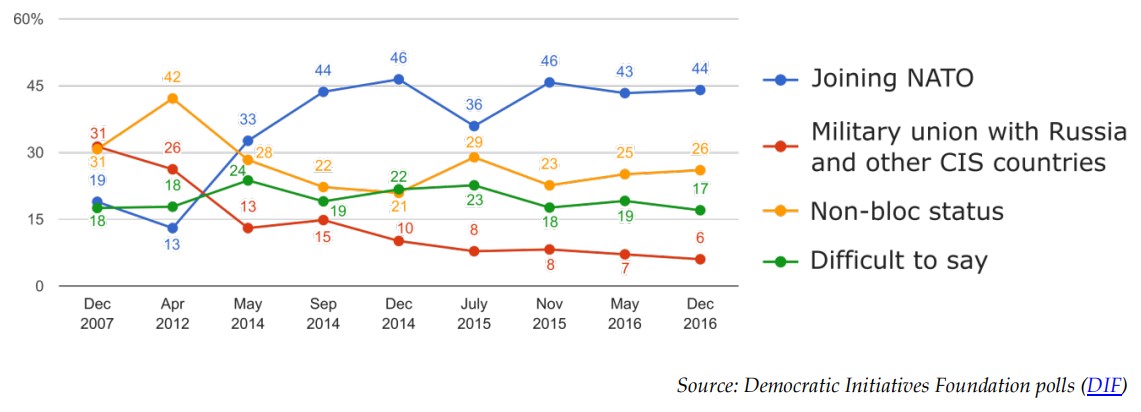

The most dramatic changes in Ukrainian foreign policy outlook since 2013 concern NATO. Supporters of joining NATO have always been in the minority in Ukraine. At some point prior to 2014, polls found that support for NATO was even lower than support for a military union with Russia (although the latter was never considered seriously by Ukrainian policymakers or experts). The option that has historically been most supported by the Ukrainian public has been non-bloc status—belonging neither to Western nor Russia-led military alliances. However, the official goal adopted by the Ukrainian parliament in 2003 during the presidency of Leonid Kuchma was to join the EU and NATO while “preserving strategic partnership” with Russia.

In July 2010, Yanukovych broke with this course. The Ukrainian parliament adopted a new law on the fundamentals of Ukraine’s foreign and domestic policy that excluded integration with NATO and established a policy of “non-alignment” aimed at appeasing the Kremlin. At the same time, EU membership was kept as a priority. However, this approach did not prevent Russia’s unprecedented economic and information attack against Ukraine in the summer-fall of 2013 when Yanukovych was working on signing the Association Agreement. Since Russia’s annexation of Crimea and aggression in the Donbas, the number of NATO supporters among Ukrainians has grown dramatically (see Figure 3).

Figure 2. Which Way of Guaranteeing the National Security of Ukraine Would Be Best? (%, Dec. 2007–Dec. 2016)

Source: Democratic Initiatives Foundation polls (DIF)

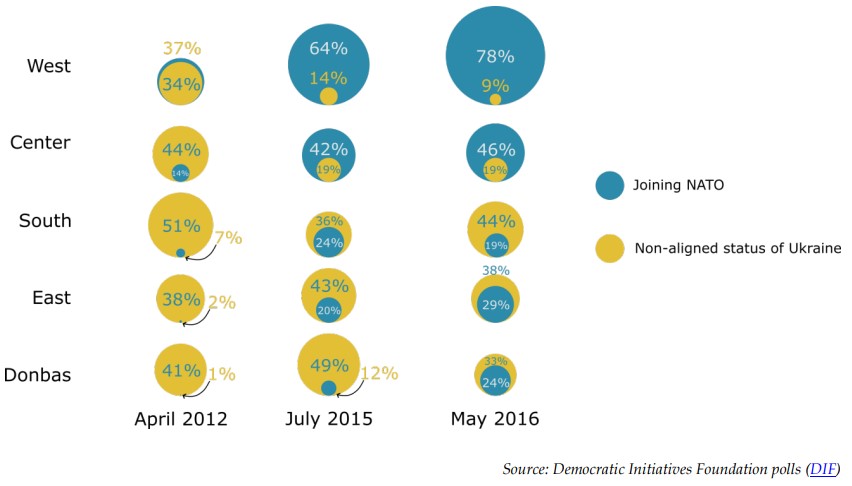

The most dramatic increase in views favoring NATO between 2013 and 2016 happened in the East and South of the country. From April 2012 to May 2016 supporters of NATO in the East increased from 2 percent to 29 percent, in the South from 7 percent to 19 percent, and in Ukrainian-controlled Donbas from 1 percent to 24 percent (see Figure 4).

Figure 3. Regional Support for Joining NATO (%, 2012–2016)

Source: Democratic Initiatives Foundation polls (DIF)

In these regions, the supporters of non-bloc status still dominate (38, 44, and 33 percent, respectively). However, they are largely demoralized and not politically active. According to a poll by DIF, if a referendum on NATO membership were held in May 2016, for those who would vote, 72 percent of those in the South would vote “yes” with 24 percent “against,” while in the East the breakdown would be 64 percent vs. 31 percent, and in Ukrainian-controlled Donbas the votes would be equally divided. Not surprisingly, in the whole country, 78 percent of those who would participate in a referendum on the matter would say “yes” to NATO and 17 percent would be “against.”

However, joining NATO is hypothetical. The problem is that although supporters of NATO prevail, a potential campaign to do so may lead to the mobilization of the anti-NATO camp, which is currently silent because of the Russian aggression in Donbas. If a NATO referendum is announced, they may become more active, and an intensive debate in the mass media may increase the turnout of those who are against NATO. Furthermore, freezing or de-escalating the conflict in the East may lessen pro-NATO attitudes. Finally, the ongoing lack of support from NATO to Ukraine in its conflict with Russia, especially if conditions worsen, could also decrease support for joining NATO.

It is safe to say that Russia’s incursions have led to changes in Ukraine’s official position about NATO. In December 2014, the new parliament (which was seated in October 2014) cancelled Ukraine’s non-bloc status and incorporated the goal of reaching the criteria necessary for NATO membership. However, Ukrainian officials are quite cautious regarding a referendum on NATO. They sense that holding it would increase the polarization of the country and catalyze anti-NATO eruptions.

There is also EU politics to consider. Kyiv does not want to irritate European decision-makers (namely in Berlin and Paris) as much as it does not want to irritate Moscow. Ukrainian officials like to point to Georgia’s experience as an impediment. In 2008, Georgians overwhelmingly said “yes” to NATO but the country, to date, has still not received a NATO Membership Action Plan (MAP). Critics of Poroshenko (and his reluctance) point out that at the July 2016 NATO summit in Warsaw, and at Georgia’s insistence, NATO reaffirmed the statement it made at the 2008 Bucharest summit that Georgia “would become a NATO member” (the same provision from Bucharest regarding Ukraine was not mentioned at the 2016 summit). The 2016 summit stressed that Georgia would receive, at some point, a MAP. In September 2016, Ukraine sent NATO an official request to join its Enhanced Opportunities Programme (which includes Australia, Finland, Georgia, Jordan, and Sweden.).

Conclusion

Before 2014, Ukrainian citizens were rather indecisive about their country’s geopolitical orientation. Many simultaneously supported deepening ties with both the EU and the Customs Union with Russia, Belarus, and Kazakhstan. However, the Euromaidan and Russia’s military campaign against Ukraine led to the collapse of support for the Eurasian vector. At present, the prevalent division in outlook is between the pro-EU camp, which is now supported by a majority of Ukrainians, and the non-aligned camp. Ukrainians are generally responsive to the European vector as they sense the EU is having a positive impact on domestic reforms. Support for NATO in Ukraine has dramatically increased. If a referendum was held today on the issue, results would show, for the first time in Ukraine’s history, significant favorability for joining NATO. This change in outlook has occurred in all regions of Ukraine, although regional differences certainly remain. For its part, the Ukrainian government officially stresses that membership in both the EU and NATO are strategic priorities. However, it is currently concentrating on what it deems to be pragmatically reachable: deepening programs of cooperation with NATO and implementing the stipulations of the Association Agreement.

Olexiy Haran is Professor at the National University of Kyiv-Mohyla Academy and Head of Research at the Democratic Initiatives Foundation, Ukraine.

Mariia Zolkina is Analyst at the Democratic Initiatives Foundation, Ukraine.

[PDF]

[1] EEU members are Russia, Belarus, Kazakhstan, Kyrgyzstan, and Armenia. Before 2014, it was the Customs Union of Russia, Belarus, and Kazakhstan.

[2] See: Olexiy Haran and Maria Zolkina, “Ukraine’s Long Road to European Integration,” PONARS Eurasia Policy Memo No. 311, February 2014.

Olexiy Haran

Olexiy Haran Mariia Zolkina, Democratic Initiatives Foundation

Mariia Zolkina, Democratic Initiatives Foundation